What Was FRANKENSTEIN Based On?

So, what was Frankenstein based on? I’ll answer your question with a question: when was Frankenstein set? And where?

In a world of Resurrectionists, surgeons, and opportunists, Frankenstein was based on everything.

Ahead of the release of Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein adaptation streaming now on Netflix, I—a former literature professor who believes Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein novel to be basically perfect—asked myself, what anyone could possibly do to improve it? Even the great Guillermo del Toro has his work cut out for him.

The only thing that would make me like Frankenstein more, I thought, is a better understanding of just how disgusting surgical practices were during the late 18th century. And to get that visually? In vivid color? Now that would be something worth seeing.

Image provided by Netflix.

The laws that led Resurrectionists to exist

Frankenstein takes place in the late 18th century, which means that the cadavers typically used in dissection were corpses of those who had been executed as criminals.

The Murder Act of 1751 stated that only the bodies of executed criminals could be used in any dissection or experiments.

To be clear, this act applied only to the UK, and the novel Frankenstein is set in Austria during this section. But, the book was released in the UK, so the contemporary audience would have been familiar with this legislature. Plus, Guillermo del Toro filmed many of these scenes in Edinburgh.

The Murder Act of 1751 was actually a liberal reform in that it did not include the number of cadavers allowed. Before this, as of 1505, the Companies of Surgeons and Barbers were only given one body to dissect per year. In 1540, that number was increased to four bodies per year.

In 1751, there was no limit on number, but the count was limited in a different way: bodies always belonged to executed criminals. The reason why? Those people’s bodies were not seen as deserving of a Christian burial.

Mutilating the body was considered immoral, but there was a more practical reason no one wanted their bodies dissected. Most Europeans at this time believed at this time that one’s actual body would be resurrected on the day of judgement, so, basically, you would need your corpse for later.

The Murder Act of 1751 was not meant to help surgeons: the Act intended to prevent murders.

It was one thing to know you could be executed. It was quite another to be condemned in the afterlife, as well.

In fact, the Murder Act of 1751 declared if you were executed, you would not be put in the ground without first being dissected.

“Resurrectionists” engraving by Hablot Knight Browne. Created in 1847 about the historical event from 1777.

“The Idle 'Prentice Executed at Tyburn: Industry and Idleness, 11” engraving by William Hogarth, September 30, 1747

Who were the Resurrectionists?

As established, the bodies that were legally available to dissect for educational purposes were fairly few in number.

In Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein, we actually get to see the doctor (Oscar Isaac) going from criminal to criminal as they wait in line to be hanged. He examines them for consideration in his experimentation, and in a literal gallows humor, he finds them all to be in poor health.

Image provided by Netflix

Three anatomical dissections taking place in an attic. Coloured lithograph by T. C. Wilson after a pen and wash drawing by T. Rowlandson.

William Cheselden giving an anatomical demonstration to six spectators in the anatomy-theatre of the Barber-Surgeons’ Company, London. Oil painting, ca. 1730-1740.

That was also the case IRL. People coming out of prison to be executed were not in excellent health, so they weren’t a great control group for anatomical study.

Dr. Frankenstein gets around this fact by poring over battlefields.

In the real world, people robbed fresh graves—not for their jewelry or riches, but for the bodies themselves.

That’s where the grave robbers got the nickname “the Resurrectionists.” They took bodies out of their graves. (They were also called “Body Snatchers,” though that moniker has been since repurposed.)

The thieves would then sell the bodies to doctors to examine. It was a grisly practice, but not nearly so bad as a practice as that of the notorious criminals William Burke and William Hare.

“The Resurrectionists” (No. 433) etching and engraving on paper by William Strang , 1898.

Burke and Hare’s notorious legacy.

Burke and Hare actually murdered people, robbed them, and then sold their corpses to doctors.

The term “burking,” where one sits on the chest of the person they are suffocating, was named after this asshole.

In case you were curious, yes, people do still steal bodies. Something like this has happened recently, actually.

Sketches from the trial of William Hare, William Burke, and an accomplice. 1829.

By the way, it’s called just “burking” and not “burke-and-hare-ing” because William Hare was granted immunity if he ratted, so he did. Which meant William Burke was found guilty and—in the best form of dramatic irony—sentenced to execution. After that, his body was subjected to anatomical experiments.

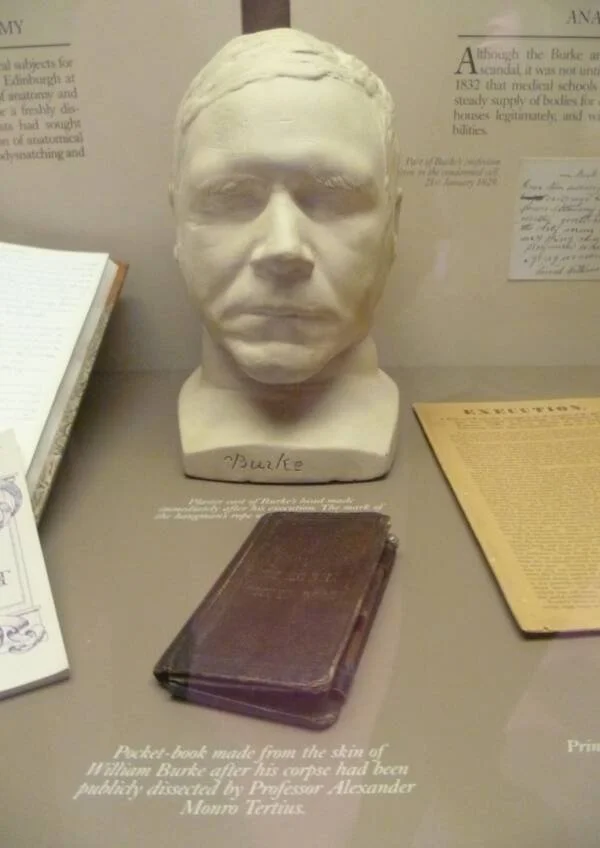

One such experiment was using his (human) tanned skin to bind a book. That very book is on exhibit in the Surgeons' Hall Museums.

Death Mask of William Burke; Pocket-book made from the skin of William Burke after his corpse had been publicly dissected by Professor Alexander Monro Tertius. Display at the Surgeons’ Hall Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

And so much more is also on exhibit there that vividly illustrates what Frankenstein was based on.

I actually visited this museum on my first visit to Scotland. I am a curious person, but I am not a squeamish person. (For reference: I watched a Vacuum-Assisted Closure (VAC) therapy, after a surgery, on someone I know, who was conscious at the time, in person, and did not flinch. A VAC is more or less when a vacuum seal is applied to help an open, sometimes-surgical wound heal from the inside out to avoid abscesses.)

So, I thought nothing of going to the museum. I was actually really excited.

If you thought the Bodies exhibit was grim… girl, I’ve never been closer to fainting than at the Surgeon’s Hall Museum. I think it’s because of the old-timey methods in which the body parts are preserved—and their disembodiment.

It was also really emotional. I almost broke when I saw the skeleton of Janet Hyslop, a woman with rickets—that’s the adult form of a Vitamin D deficiency. Her legs were completely twisted beneath her because of the disease, and she was doomed to die the moment she got pregnant because the disease had so narrowed her pelvis. (You can read about her heroism and how she contributed to modern obstetrics here in The Scotsman.)

I recently learned that she likely was not asked if her remains could be dissected or put on display.

And they are, definitely, on display. Maybe that’s why my stomach is turning just writing this. It’s giving Henrietta Lacks. It’s giving medicalized torture.

That said, a case might be made that it honors the people more if their bodies are used for education—now that they’ve already been dissected. After all, there are now teams of highly trained specialists who take very good care of everything, even if the original handlers did not.

The Surgeon’s Hall Museum is definitely worth a visit if you find yourself in Edinburgh, and you should at some point definitely find yourself in Edinburgh.

Even Guillermo del Toro loves Edinburgh.

The Surgical Theater

That same museum showcases Edinburgh’s unique contribution to surgical practice, especially in the History of Surgery Museum. It features a dedicated “Anatomy Theatre” complete with dissection table. (I haven’t visited this location, but there’s another Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret in Southwark, London, too.)

Up until fairly recently, the only way to see how a dissection happened was to actually see it happening. That meant an arena-like room where the surgeons would teach the audience as they performed surgery… before anesthesia existed. And before antiseptic practices.

A Surgical or Anatomy Theater is where Victor Frankenstein presents his case of reanimation to the other surgeons. This was my absolute favorite scene because it seemed so authentic—minus the reanimation, I mean.

Image provided by Netflix

The anatomy theatre at Leiden University, early 17th century

“The Reward of Cruelty (The Four Stages of Cruelty),” Third State of Three, etching and engraving by William Hogarth, February 1, 1751.

To be clear: surgical theaters do still exist for student doctors. They’re much more sanitary now, patients are under anesthesia, students can attend operations regularly, and technology allows procedures to be viewed in other ways, too.

Image provided by Netflix

Patronage to develop scientific theory

One of the less immediately scary parts of Frankenstein, too, is that Victor gets private funding. That in itself is not scary—private funding sounds awesome! Who among us would not love to have a patron!?—but in practice, it allows people with money to practice instead of people with merit.

Suffice it to say that Frankenstein’s reanimation concept got prioritized because Heinrich Harlander (Christoph Waltz) wanted that technology. There were probably other concepts presented in that surgical theater that didn’t get hand-picked because they didn’t directly benefit someone who could fund the project.

I mean, how easy would it have been to get some Vitamin D to Janet Hyslop, if anyone knew that’s what she needed? But alas, someone who couldn’t afford proper nutrition probably couldn’t bankroll the research, either.

Other historical context that helps to really create the vibe of the very first science fiction novel.

Frankenstein really embodies the horror of the age in which it is set… but Guillermo del Toro also updates the horror to be “of its time.”

In a world where people create sentience all the time without a second thought, the quote will always ring true,

“I never considered what would come after creation.”

“Victor Frankenstein observing the first stirrings of his creature.” Engraving by W. Chevalier after Th. von Holst, 1831.

If this story stayed with you, you might also like:

→ CRIMES OF THE FUTURE...You Mean The Medicalized Torture Of The Past?